CANCER

Lung cancer – Is there a role for screening?

Despite considerable interest in developing a screening tool to detect early-stage lung cancer, lung cancer screening remains very much a controversial issue

May 1, 2013

-

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide.1 It is also the leading cause of cancer mortality in Ireland, representing approximately 20% of all deaths due to cancer.2 Despite advances in therapy, five-year survival rates average approximately 16% for all patients with lung cancer.3 These poor survival figures, coupled with the success of screening to improve the outcomes in cervical and breast cancer, have been the impetus for studies to develop an effective lung cancer screening test. Despite considerable interest in developing a screening tool to detect early-stage lung cancer, lung cancer screening remains very much a controversial issue.3

Cancer screening

The goal of cancer screening is to identify asymptomatic patients with unrecognised symptoms and to identify those at increased risk. The concept of screening is based on the assumption that identifying and treating cancer in asymptomatic individuals will prevent cancer or improve survival. This assumes that there is a treatable phase of pre-cancer or cancer that, if left untreated, would progress. It also assumes that early treatment improves outcome compared with late treatment.

The important outcome for cancer screening is its impact on overall mortality. Therefore, screening should benefit the individual by increasing life expectancy, as well as increasing quality of life.

In the ideal screening, the rate of false-positive results (ie. screening that shows there is cancer present when in fact there is not) should be low to prevent unnecessary testing. The large fraction of the population should not be harmed (ie. low risk) and the screening test should not be so expensive that it places an onerous burden on the healthcare system.3 Thus, the ideal screening should:

- Improve outcome

- Be scientifically validated (eg. have acceptable sensitivity and specificity)

- Be low risk, reproducible, accessible and cost-effective.3

Lung cancer screening

Currently, most lung cancers are diagnosed clinically when patients present with symptoms, with approximately 75% of patients presenting with advanced local or metastatic disease that is not amenable to cure.4 Screening for lung cancer has the potential to identify the disease in the earlier stages of development and to reduce the risk of death.

Current available options for lung cancer screening include sputum cytology, chest radiograph (CXR) and low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scanning.

Sputum cytology and chest x-ray

Several early controlled trials of sputum cytology and CXR screening for lung cancer have been performed. While these studies have shown that early detection of lung cancer is possible with such initiatives, there was no reduction in the number of advanced lung cancers detected or in the number of lung cancer deaths.5-12

Low-dose CT scan

Renewed enthusiasm for lung cancer screening came with the advent of low-dose CT (LDCT) imaging, which has the ability to detect smaller tumours than on CXR. Key questions in relation to screening for lung cancer with LDCT include:

- What are the potential benefits and potential harms of screening individuals at increased risk of developing lung cancer using LDCT?

- Which groups are most likely to benefit or not benefit from screening?

- In what setting is screening likely to be effective?

To establish the benefit of LDCT in lung cancer screening, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) in the US enrolled current or former heavy-smokers and compared LDCT with standard CXR. Primary results have been published showing that participants who received LDCT scans had a 20% lower risk of dying from lung cancer than participants who received standard CXR. However, there was a high rate of false-positive results.13

It should be noted that this population of smokers at high-risk for lung cancer was a highly motivated and primarily urban group, screened at major medical centres. These results alone, therefore, may not accurately predict the effects of recommending LDCT scanning for other populations.

Potential harm

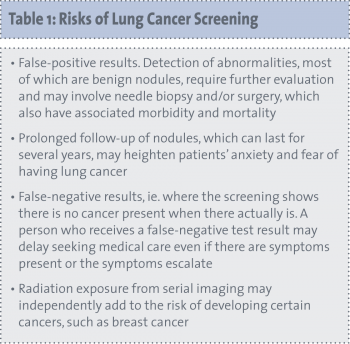

In theory, screening for lung cancer has the potential to reduce mortality and morbidity. There are potential harms, however, attached to screening as well as potential benefits. These risks need to be appreciated in order to determine the benefits (see Table 1).

Cost-effectiveness

It is also important to consider the cost-effectiveness of lung cancer screening. LDCT scanning is more expensive than many other screening programmes. Each LDCT scan for lung cancer is approximately two to three times more expensive than a mammogram for breast cancer screening.3

Lung cancer screening can also lead to the detection of diseases other than lung cancer such as infection or coronary artery calcification, as well as renal, adrenal and liver lesions. Although detection of other diseases may frequently provide a clinical benefit to the patient, costs will be further increased with additional testing and treatment.3

While the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) demonstrated that LDCT screening reduces mortality in a high-risk population, the cost of screening per life saved is unknown, but is likely to be high, given the high false-positive rate leading to the need for additional studies, the need for ongoing screening, and the relatively low absolute number of deaths prevented (73 per 100,000 person years).3,13

Clinical practice guidelines

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recently come out in favour of lung cancer screening for high-risk patients in a new set of guidelines.3 The NCCN recommends screening with LDCT for high-risk individuals who are aged 55-74 years, have a > 30 pack-year smoking history, and former smokers having quit within 15 years.3 Screening is also recommended for high-risk individuals aged > 50 years, have a > 20 pack-year smoking history and one additional risk factor. These additional risk factors include a cancer history, lung disease history, family history of lung cancer, radon exposure and occupational exposure.3 Screening is not recommended for low-risk or moderate-risk individuals.3

In addition, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recently issued two recommendations in relation to LDCT screening for lung cancer:14

- For smokers and former smokers ages 55-74 who have smoked for 30 pack-years or more and either continue to smoke or have quit within the past 15 years, ASCO suggests that annual screening with LDCT should either be offered over both annual screening with CXR or no screening, but only in settings that can deliver the comprehensive care provided to NLST participants

- For individuals who have accumulated fewer than 30 pack-years of smoking, are either younger than 55 or older than 74, or who quit smoking more than 15 years ago, as well as for individuals with severe comorbidities that would preclude potentially curative treatment and/or limit life expectancy, ASCO suggests that CT screening should not be performed.

Conclusion

Lung cancer screening is a rapidly evolving field, with the potential to significantly reduce the burden of lung cancer. It is also a complex and controversial issue with inherent risks and benefits.

Having a validated screening test for lung cancer should not be seen as replacing ongoing efforts to control smoking. Cancer prevention through the promotion of smoking cessation is likely to have a far greater impact on lung cancer mortality than screening. For those who wish to prevent deaths from cancer, respiratory or heart disease, the first step is to quit smoking.

While LDCT screening may benefit individuals at an increased risk for lung cancer, it is also a clinical intervention still in its infancy. Many questions that clinicians and patients may reasonably ask when considering whether to pursue screening, such as the cost-effectiveness and true risk-to-benefit ratio, are as yet unanswered. Neither is it known what effect lung cancer screening will have on the quality of life of patients.

Further studies are needed to determine the actual cost-effectiveness of LDCT and to establish the optimal frequency and duration of screening.

As policies for implementing lung cancer screening are designed, a focus on multidisciplinary programmes (incorporating medical oncologists, respiratory physicians, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, and pathologists) will be helpful in order to minimise interventions in benign lung disease and in order to optimise future screening decision making.3

References

- WHO. Cancer Fact Sheet No 297. October 2011. Available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/

- Irish Thoracic Society lung cancer sub-committee. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. Third edition 2009. Available at www.irishthoracicsociety.com/images/uploads/file/ITSLungCancerGuidelinesFebruary2010.pdf

- National Cancer Comprehensive Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Lung Cancer Screening 2011. Available at www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/lung_screening.pdf

- Molina JR, Adjei AA, Jett JR. Advances in chemotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2006; 130(4): 1211-1219

- Flehinger BJ et al. Screening for lung cancer. The Mayo Lung Project revisited. Cancer 1993; 72(5): 1573-1580

- Fontana RS et al. Early lung cancer detection: results of the initial (prevalence) radiologic and cytologic screening in the Mayo Clinic study. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984; 130(4): 561-565

- Kubík A, Polák J. Lung cancer detection. Results of a randomized prospective study in Czechoslovakia. Cancer 1986; 57(12): 2427-2437

- Kubík AK, Parkin DM, Zatloukal P. Czech study on lung cancer screening: post-trial followup of lung cancer deaths up to year 15 since enrollment. Cancer 2000; 89(11 Suppl): 2363-2368

- Marcus PM et al. Lung cancer mortality in the Mayo Lung Project: impact of extended follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92(16): 1308-1316

- Payne PW, Sebo TJ, Doudkine A, et al. Sputum screening by quantitative microscopy: a re-examination of a portion of the National Cancer Institute Cooperative Early Lung Cancer Study. Mayo Clin Proc 1997; 72(8): 697-704

- Melamed MR. Lung cancer screening results in the National Cancer Institute New York study. Cancer 2000; 89(11 Suppl): 2356-2362

- Tockman MS, Mulshine JL. Sputum screening by quantitative microscopy: a new dawn for detection of lung cancer? Mayo Clin Proc 1997; 72(8): 788-790

- Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. NEJM 2011; 365(5): 395-409

- American Society of Clinical Oncology and American College of Chest Physicians. The role of CT screening for Lung Cancer in clinical practice. The evidence based practice guideline. Available from www.asco.org/institute-quality/role-ct-screening-lung-cancer-clinical-practice-evidence-based-practice-guideline